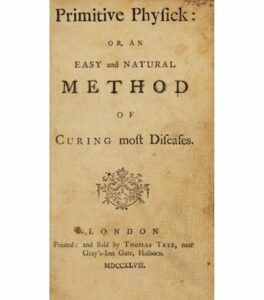

Primitive Physick: or, an Easy and Natural Method of Curing most Diseases by John Wesley

A fundamental text for the Methodists, which Still’s father surely knew and probably owned - in addition to remedies, the book contains a preface that dispenses advice for a healthy life.

Publisher: Thomas Trye, London, UK

Publisher: Thomas Trye, London, UK

Year of publication: 1747

Number of pages: first edition: 128 pagine.

Wesley made corrections and additions to all the editions following the first, keeping pace with the progress of both medicine and science.

In particular, in the fifth edition published in 1755 he inserted some footnotes and marked some remedies as “tried and tested”. Over the years he advised ever less aggressive or dangerous remedies and in the ninth edition (1761, 136 pages) he introduced the therapy with electricity. In the 15th edition, published in 1772, he marked his favorite recipes with an asterisk. In a postscript at the bottom of the 1781 edition (the twentieth one, 132 pages) Wesley explains that he made changes to the text and omitted some parts following doctors’ criticisms (Madden, 2007).

Description of the book and comment:

In the preface to the first edition, Wesley explains that he wanted to collect a series of inexpensive and easily available remedies useful for treating many diseases, consulting only “experience, common sense and the common interest of humankind” (Wesley, 1747: xiv).

For each ailment provides more than one remedy, advising to start from the first and, if after a certain time it does not work, to move on to the next. He points out that men do not all react in the same way, so remedies do not work in the same way on all people, nor on the same person at different times. However, remedies deemed infallible are marked with the letter “I”.

In addition to taking the medicine, Wesley recommends a healthy lifestyle: follow a simple and not abundant diet, refrain from aged foods, drink only water or at most low-alcohol beer, exercise – all expedients these to be added to prayer and faith in God, who kills and vivifies, who leads to the tomb and resurrection (Wesley, 1747: xix).

Wesley also reports some recommendations, mostly taken from the works of Dr. George Cheyne, his personal physician and interesting figure of nineteenth-century philosopher, proponent of physical exercise and healthy eating (see p. es. Siddall, 1942). Wesley recommends hygiene and cleanliness of the house and clothes, healthy air and a light diet. He claims that water is the best drink, that strong alcohol is a poison, that tea and coffee are harmful to people with weak nerves. It is recommended to lie down early and get up at dawn, and to do daily exercise in the fresh air, without exaggerating. Advise who should read or write a lot to learn to do so while standing, otherwise they will damage their health. Highlights the benefits of cold baths, also for healing purposes (Wesley, 1747: xix-xxiii).

According to Wesley, passions have a much greater influence on health than people can imagine. In fact, he writes that all violent and sudden passions cause acute illnesses, while the passions lasting over a period of time, like for example pain and hopeless love, cause chronic diseases. Moreover, he states that medicines are useless until the passion underlying the disease is sedated (Wesley, 1747: xxiii).

Wesley ends the preface by asserting that the love of God is not only the sovereign remedy for all suffering but also a preventive factor that, keeping the passions within the peroper limits, prevents the onset of diseases. For this reason it is the most powerful element for promoting health and the attainment of old age, as it confers “an unspeakable joy and perfect calm, serenity and tranquility” to the mind (Wesley, 1747:xxiv).

Strengths: the interest and importance of the volume for the history of osteopathy can be found mainly in the preface. Wesley’s ideas permeated A.T. Still’s childhood through the words and works of his father Abram, an itinerant Methodist pastor.

Weaknesses: the volume has no index, but presents the diseases and their remedies in alphabetical order.

Wesley had cutting-edge ideas in regard to prevention and healthy lifestyle, yet his focus on social justice, human well-being, and hygiene was embedded in the custom: in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries England it was usual for pastors and aristocrats to dispense advice to the inhabitants of rural villages, too far from urban centers or too poor to call a doctor. Though he did not have a medical degree, Wesley had read and studied many books on anatomy and medical science, for example the works of Hermann Boerhaave, Thomas Syndham, George Cheyne, William Cadogan, Samuel Tissot, Richard Mead, and John Huxham (Hughes, 2008). His advice, which may seem absurd today, did not differ too much from the prescriptions of the doctors of the time (Rogal, 1978).

Motivated by a sincere interest in relieving the suffering of the poor, in 1746 Wesley opened a dispensary in Bristol where, with the help of a pharmacist and a surgeon, he offered free care and medications. It was in this very spirit that he wrote this volume (of which he did not appear as the author until 1760), with the intention of reaching all the wretched of the earth (Rousseau, 1968). The prescriptions of doctors had become very complex and therefore expensive, making the less wealthy social classes unable to cure themselves. By distributing simple tips based on easy-to-find remedies, Wesley sought to give each person power over their own health (Skinner & Schneider 2016).

Wesley’s book was a great success, but attracted much criticism to its author: the medical class accused him of charlatanism, the religious kept him at a distance harboring suspicion about the extremism of his evangelical revivals, while the best society blamed him as a populist.

Certainly the book was not one of its kind: in England alone, there were many examples of similar publications containing medical advice, published in the previous and subsequent decades (Rogal, 1978), like the following:

- 1671: John Archer Every Man His Own Doctor

- 1681: William Welwyn Physick for Families

- 1733: George Cheyne The English Malady

- 1742: George Cheyne The Natural Method of Curing the Diseases of the Body and the Disorders of the Mind

- 1744: Bemard Lynch Guide to Health

- 1760: Hugh Smith Family Physician

- 1769: William Buchan Domestick Medicine

- 1778: Alexander George Gordon The Compleat English Physician

- 1778: Lewis Robinson Every Patient His Own Doctor

- 1780: Robert Dalton Every Man His Own Physician

- 1785: Charles Hall Medical Family Instructor

To this day, the remedies recommended by John Wesley have only an exclusively historical value, instead the philosophy behind his approach is still at the center of numerous volumes and articles that recognize the common sense and feasibility in the field of contemporary medical epistemology (For example, see the short bibliography at the bottom of this page).

According to some, Wesley’s approach, patient-centred and empirical, aimed at influencing issues such as access to, availability and cost of healthcare, already had a political and cultural value at the time, which is still applicable to the present day (Skinner & Schneider 2016). Along the same lines others believe that the practice of pietas and the religious devotion of Wesley are based on a holistic idea, in which they recognize a social message addressed to ordinary people in order for them to take back responsibility for their own health – but also the proposal of an integrated medicine able to cure the body, mind and spirit (Hughes, 2008).

Among the many other scholars of Methodism, there are those who claim that interest in health and medicine was intrinsically linked to Wesley’s theological thought, and see there a possible holistic health model that could be fruitfully applied by the religious people of his time. Wesley emphasized that it was possible to experience divine salvation in the present moment even during life, while at the time many Christians were convinced that they would obtain the healing of the soul and body only through resurrection (Maddox, 2007).

Wesley’s great interest in the care of the body often led him to use metaphors based on medical language to explain theological concepts, for example referring to Jesus as the “great Physician of the soul”. Far from bringing the health of the body and the health of the soul to the same level, he saw a remarkable correlation between the two of them (Oct, 1995:180).

A.T. Still may have picked up on several aspects of Wesley’s message, such as his intolerance of gibberish, his criticism of doctors prolonging treatment to increase their earnings, his repulsion towards alcohol, his preference for simple foods, the habit of raising at dawn and his conviction of the benefits of exercise.

On a deeper level, the reading of Wesley’s sermons may have led Still to accept the idea – however widely spread at the time – that nature and therefore the human body were subject to mechanical principles. For example, Dr. Cheyne had stated that “all body ailments and disorders … are due to a defect in the quantity, quality or movement of fluids, or to an incorrect disposition and consistency, to a distortion, distension, dislocation or laceration of the … conduits” (Cheyne, 1744:4-5).

Finally, trying to explain the origin of all diseases, Wesley himself had hypothesized in one of his sermons (“The Image of God”) that the fruit of the forbidden tree had released into the human body particles that with time had begun to adhere to the tunics of the blood vessels, creating obstructions that prevented the free flow of blood (Oct, 1995:189).

The volume has no index but presents the diseases and their remedies in an approximate alphabetical order.

Cheyne, G. A new theory of acute and slow continu’d fevers together with an essay concerning the improvements of the theory of medicine. 6° ed. Londra: George Strahan, 1744.

Hughes, M. D. (2008). The holistic way: John Wesley’s practical piety as a resource for integrated healthcare. Journal of religion and health, 47(2), 237-252.

Madden, D. (2007). A Cheap, Safe and Natural Medicine: Religion, Medicine and Culture in John Wesley’s Primitive Physic (Vol. 83). Rodopi.

Maddox, R. L. (2007). John Wesley on holistic health and healing. Methodist History, 46(1), 4-33.

Malony JR, H. N. (1996). John Wesley’s Primitive Physick: An 18th-century Health Psychology. Journal of Health Psychology, 1(2), 147-159.

Ott, P. W. (1995). Medicine as metaphor: John Wesley on therapy of the soul. Methodist history, 33(3), 178-192.

Rogal SJ. Pills for the poor: John Wesley’s Primitive Physick. Yale J Biol Med. 1978 Jan-Feb;51(1):81-90.

Rousseau GS. John Wesley’s “Primitive Physic” (1747). Harv Libr Bull. 1968 Jul;16(3):242-56.

Siddall, R. S. (1942). George Cheyne, MD: Eighteenth Century Clinician and Medical Author. Annals of Medical History, 4(2), 95.

Skinner, D., & Schneider, A. (2019). Listening to Quackery: Reading John Wesley’s Primitive Physic in an Age of Health Care Reform. Journal of Medical Humanities, 40(1), 69-83.

Wesley J. (1747) Primitive physick: or, an easy and natural method of curing most diseases. Thomas Trye, Londra, UK.

Are you an osteopath?

Register and enjoy the membership benefits. Create your public profile and publish your studies. It's free!

Register now

School or training institution?

Register and enjoy the membership benefits. Create your public profile and publish your studies. It's free!

Register now

Do you want to become an osteopath? Are you a student?

Register and enjoy the membership benefits. Create your public profile and publish your studies. It's free!

Register nowHistorical osteopathy books

Osteopathy Research and Practice by Andrew Taylor Still

The fourth book of A.T. Still, written at the age of 82 years, enunciates the principles and the practical maneuvers of osteopathy in reference to the single pathologies, classified by body regions.

ReadHistory of Osteopathy and Twentieth-Century Medical Practice by Emmons Rutledge Booth

A milestone in the history of osteopathy. Emmons Rutledge Booth, who enrolled at the ASO in Kirksville in 1898 and graduated in 1900, met A.T. Still personally.

ReadPhilosophy of Osteopathy by Andrew Taylor Still

The second book published by A.T. Still, it collects the basic principles of osteopathy, written over several years and then gathered in one volume. Despite the insistence of his friends, Still was not sure that the time was ripe to divulge his early science.

ReadAutobiography of Andrew Taylor Still with a History of the Discovery and Development of the Science of Osteopathy by A. T. Still

A fundamental text to begin to know the founder of osteopathy and to understand the cultural context and the historical events during which his life unfolded.

ReadThe Old Doctor by Leon Elwin Page

A small volume dedicated to the story of Andrew Taylor Still, and to the birth and development of the idea of osteopathy.

ReadThe Cure of Disease by Osteopathy, Hydropathy and Hygiene A Book for the People by Ferdinand L. Matthay

A small volume addressed to the general public, dispensing health advice and illustrating some osteopathic techniques.

ReadOsteopathy; the New Science by William Livingston Harlan

The volume collects and comments a series of relevant articles on the new science of osteopathy, highlighting legal, historical and theoretical aspects.

ReadA Manual of Osteopathy – with the Application of Physical Culture, Baths and Diet by Eduard W Goetz

Very schematic volume, with the aim of spreading the osteopathic application techniques to everybody, even to those lacking any sort of health training.

ReadOsteopathy Illustrated: a Drugless System of Healing by Andrew Paxton Davis

A substantial and in-depth volume, written by a physician who participated in the first course of the ASO and then tried to integrate osteopathy into other care systems like chiropractic and neuropathy.

Read