Francesca Galiano | 23/03/2023

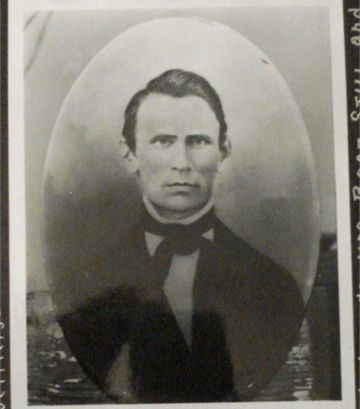

Abram Still, father of the founder of osteopathy

August 25, 1796, Buncombe County, North Carolina, USA, – December 31, 1867, Centropolis, Franklin County, Kansas, USA, , MD

August 25, 1796, Buncombe County, North Carolina, USA, – December 31, 1867, Centropolis, Franklin County, Kansas, USA, , MD

Abram Still was a Methodist circuit rider (an itinerant preacher), physician, and ardent abolitionist.

According to the chronicles, Abram Still’s grandfather, who left England, arrived in North Carolina with five brothers and settled in Buncombe County, where he started a family and had eight children.

One of these was Boaz Still, jokingly nicknamed “dwarf” because he weighed almost two hundred pounds. He married Mary Lyda, an energetic frontier woman of Dutch and American Indian descent, known for her ability to use a rifle to kill wild animals.

Boaz loved whiskey, racehorses and cockfighting. He established a plantation that exploited slave labor, where he lived with Mary, who gave birth to 15 children, eight girls and 7 boys. Five of these, including Abram, became physicians. Abram Still converted to Methodism, perhaps on the occasion of a camp meeting, and began to nurture increasingly strong abolitionist ideas, which later led him to break off all ties with his family of origin.

Ordained a Methodist pastor, in 1818 Abram began itinerant preaching in the Tazewell Circuit, a mountainous region in southwestern Virginia. Nature offered astonishing panoramas, but the climate could be very harsh, with inclement winds. Abram, described as tall, resolute and good-looking, met Martha Poage Moore, daughter of a Methodist family who lived in a secluded cabin in Abb’s Valley. He married her in 1822.

Their first son, Edward, was born in 1824, and the following year Abram was ordained a senior member of the congregation and moved to Jonesville, Lee County, also in Virginia, in the foothills of the Cumberland Mountains. Abram bought five hundred acres of land, built a log cabin (now rebuilt and preserved in the Kirksville Museum), and for the next ten years farmed, practiced medicine, preached, and organized camp meetings in order to convert more people to the Methodist faith. Three more children were born in Jonesville: James (1826), Andrew Taylor (1828), and Barbara Jane (1830).

The life of the Methodist preacher, who always had to prioritize the needs of the Church over his own and those of his family, was very hard: half of the “circuit riders” died before the age of thirty-three. Abram stayed away from home for periods of several weeks, the time it took him to cover the “circuit” assigned to him on horseback and visit the farms scattered throughout the territory. He would always carry a copy of the Bible with him, but also Wesley‘s medical manual (entitled Primitive Physick) and medicines for the therapy of the faithful, since the Methodists considered it important to take care of the body as well as the soul of their followers. Since he had the title of doctor, Abram also practiced the orthodox medicine of the time, administering “heroic” remedies such as bloodletting, violent purges and calomel, a mercury-based compound that was dispensed until the first symptoms of poisoning.

In line with the principles of Methodism, Abram was against alcohol, gambling, card games, dancing, the display of jewelry, and the trading of slaves. He urged the faithful to help others, feed the hungry, clothe the naked and visit the sick.

In 1834 he moved his family to New Market in the state of Tennessee. The town then had only 250 inhabitants, but the children were able to attend school. In the following years, the issue of slavery became increasingly thorny within the Methodist Church: the launch of plantations and the influx of African American labor helped to make the calls of the abolitionists less and less popular.

After an adventurous seven-week journey, during which the children marveled at watching a steamboat on the Mississippi and Abram recklessly lent a Methodist pastor all the money entrusted to him by the Church so that he could support himself for the first year, they arrived in the new county, formed shortly after the land parcel definitions had been concluded.

Abram was the first Methodist pastor in northeast Missouri, and he was also the physician who wrote the first prescription in the sparsely populated wilderness. He built a log cabin and started working on the farm. At the end of the spring, after helping to start the crops, he used to go on horseback to visit the faithful of the great circuit for which he was in charge.

Without the money entrusted to them by the Methodists and having used up all of Martha‘s savings, the family of now nine children survived struggling to get hold of even the basic necessities. For Abram, religion had absolute priority: in addition to preaching, he organized a camp meeting so that his children John and Mary were officially welcomed into the religious community. In fact, there were rumors of the imminent end of the world, and Abram wanted to be sure that they would go to heaven.

As tobacco cultivation spread, plantations and the exploitation of African American labor also increased in Missouri. Abram, who made no secret of his abolitionist ideas nor gave up activism to spread such ideas, found himself in an increasingly awkward situation: in the schism that divided the Methodists he sided with the Northern Church.

In 1851, social tensions increased to such levels that Abram’s life seemed to be in danger, so the congregation entrusted him with the task of founding and managing the Wakarusa mission in Kansas, in a territory still not accessible to whites. Abram left with his wife and six children (the already married boys, Andrew, Edward and Barbara Jane remained in Missouri) in March 1852, with the aim of preaching and teaching to a small group of Indians converted to Christianity and opposed to slavery, belonging to the Shawnee tribe who seventy-five years earlier had exterminated and tortured several members of Martha‘s family in the Abb’s Valley massacre. Deeply religious and aware of her obligations to the church and her husband, Martha accepted with resignation and not without concern her transfer to the mission, which turned out to be less burdensome than expected since the Indians living there had already been in contact with the whites before. The missionary experience ended shortly after, when the territory on which it stood was sold to the Indians in 1853.

In 1854 Abram settled near the newborn town of Lawrence and, in addition to continuing his preaching and practicing medicine, actively participated in the riots that bloodied Kansas before the Civil War, made new friends with antislavery immigrants from the east coast and, together with his sons, collaborated with John Brown and Major Abbott during the abolitionist armed operations. According to some unconfirmed rumors he may have joined the Underground Railway, which offered a series of secret shelters to runaway slaves. Kansas was annexed to the Union in January 1861, just a few months before the outbreak of the Civil War.

As Abram got older he stopped being a traveling preacher, however he always remained active in churches and congregations. In recent years he moved to Centropolis, where he lived on a small farm with his wife Martha. On Christmas Day 1867 he was called to deputize for a minister and decided tto go even though he was unwell. He gave a memorable sermon, however a few days later he contracted acute pneumonia.

On his deathbed, surrounded by his family, he began summoning unconverted neighbors, hoping to convince them – and in at least one case he seems to have been successful.

At one point he asked Andrew if he thought he could recover, and got a negative answer. When his son asked him what he knew about the afterlife, he confided that he felt in the hands of a merciful God, but that apart from that it was like taking “a leap in the dark”. He passed away at seventy-one years of age.

- Booth ER. (1924) History of Osteopathy and Twentieth-Century Medical Practice. Cincinnati, OH: Caxton Press; 1924.

- Beougher T.K. Camp Meetings and Circuit Riders: Did You Know? Little Known Facts about Camp Meetings and Circuit Riders, Christian History, Issue 45: Camp Meetings & Circuit Riders: Frontier Revivals, 1995.

- Museum of Osteopathic Medicine, ref. 1979.269.16, “Martha Poage Moore Still”.

Trowbridge C. Andrew Taylor Still. The Thomas Jefferson University Press, Northeast Missouri State University, Kirksville, 1991. - Wesley, J. (1747). Primitive physic, or An easy and natural method of curing most diseases London: Thomas Trye.

The itinerant preachers were hosted by the faithful along their way, who also provided for their food. To distinguish themselves from potential profiteers, they wore a medal of recognition attesting to their belonging to the Methodist Church.

Are you an osteopath?

Register and enjoy the membership benefits. Create your public profile and publish your studies. It's free!

Register now

School or training institution?

Register and enjoy the membership benefits. Create your public profile and publish your studies. It's free!

Register now

Do you want to become an osteopath? Are you a student?

Register and enjoy the membership benefits. Create your public profile and publish your studies. It's free!

Register now